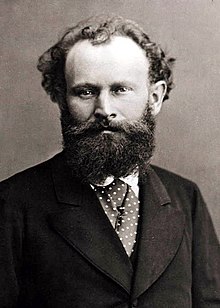

If you would like to see his work, please link to: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/%C3%89douard_Manet

It is a beautiful scene which, at first glance, seems to celebrate everything marvelous about the Belle Epoch, embracing the rich abundance of modern Paris in a beautiful, newly designed city of glittering electric light. It is a scene which could have been contemporarily captured by a photograph, or printed in a newspaper, or posted as an advertisement on one of the modern buildings lining the wide, tree-shaded boulevards of the newly self crowned cultural capital of the world.

In the glare of a room filled with those modern, electrified lamps, a young woman stands behind a counter laden with the ingredients of a night of merry frolic. Her outstretched arms, leaning lightly on the marble surface, form a triangle, which directs us to examine what she has on offer. By her left hand, a crystal compote is filled with fresh citrus, which begs to be squeezed, zested and curled into cocktails. A mysterious vessel of green liqueur tempts us with the flavor of something mysterious and possibly dangereux. At her right hand, a bottle of garnet colored wine is perfectly aged. Adjacent beer and champagne bottles are tastefully aligned, daring her to pop their corks in a fizzy release. In between the two groups of aperitifs stands a small crystal vase holding delicate, softly petaled roses; like the girl, they are in full bloom.

The flowers are silhouetted against a dark velvet jacket, accenting the barmaid's corseted waist. The revealing sweetheart neckline of the jacket is trimmed with a frill of lace, and a small spray of flowers is placed just above the contrasting center buttons, both hiding and highlighting her decolletage. The practical three quarter length sleeves of her jacket, also accented with upturned lace, reveal strong, sturdy arms, and hands ready to serve our needs and desires. A brassy golden bracelet and velvet choker with locket complete the outfit, complimented by delicate pearl earrings. The girl's forehead is hidden by a thick fringe of almost too long bangs, which reflect back the glassiness of the overhead lights.

Behind the bar is a large mirror, which silently reveals to us a room that must certainly be cacophonous. The silvery image depicts a large hall, crowded with lively, fashionable patrons. Some are conversing, others are walking between the tables, and, among the cigar smoke, there is wave after wave of shining silk top hats. To our left, one woman is seen peering through opera glasses at what is revealed at the upper corner to be a pair of tiny green booted feet, delicately balanced atop a swinging trapeze bar.

On the right, the mirror reflects the velvety peplumed back of the barmaid's jacket, the casualness of her ponytailed coiffure, and the face of her well heeled, mustachioed patron as he leans in to place his order.

But even in the beauty and vibrancy of the scene, something seems slightly amiss.

First, the girl: anyone who has ever been a server will instantly recognize Suzon's expression of disengaged detachment. Her eyes seem to both meet and evade our own. In her expression, she vacillates between being ready to engage and serve, and being lost in her own thoughts.

The space behind the bar is also excessively narrow, with barely enough room for Suzon's sideways passage. She does not appear to have enough area to even turn around.

The final oddity in the painting is the mirror, which puzzles the viewer in several different ways. First, the bottom of the mirror is not linear, and seems to stair step down an inch or so in the space behind Suzon's body. The reflection of the bottles on the bar are also off, with the "real" bottles aligned in a row, and the reflected bottles presented in a zig zag.

But most disturbing of all is the reflection of Suzon and her patron. If the mirror were real, then Suzon's back would be reflected directly behind her, in which case the reflection of her back would be obscured by her own presence. The patron she engages (who should be seen in the position of us, the viewers) is instead seen on the far right of the picture, and this juxtaposition further compounds the visual confusion.

But we don't care….

The Bar at the Folies-Bergere (1882) succeeds because in it, Manet makes several significant creative leaps:

First, Suzon's large grey-blue eyes are not vacant, as some have argued, but belong instead to her own interior thinking. She may be considering a proposal by her boyfriend, or an unfortunate unplanned pregnancy, or that she stupidly wore the wrong, uncomfortable shoes to work that night. It does not matter. Manet tenderly lets her keep her own thoughts to herself, which gives her a dignity as great as that of any queen. Manet does not tell us her story, but instead allows us to draw our own conclusions. This makes Suzon all of us, and all of us Suzon. This makes The Bar a painting not only about a scene, but, significantly, allows us to feel something about that scene.

Like the space behind the bar, our modern world may at first appear expansive, and, thanks to careful urban planning, look like there is plenty of room, but that very modernity comes with a price - a tension that is caused by the narrowing in of an increasingly complex and faster paced society. The smoke and mirrors that we see in the scene is just that: smoke and mirrors covering what can be a complicated and increasingly stressful world within a city of rapidly increasing population, density, and urban crowding.

And finally to the mirror itself: Manet uses it to show us that we no longer need to make perfect "photographic" paintings in order to make art. The art can, of it's own accord, convey a mood, an emotion, or a feeling about the subject, without having to conform to antiquated rules codified only to keep artists and the production of art in a perpetual looping cycle of documentation.

The weirdness of Manet's composition, particularly with regard to the mirror, is why the painting works. Suzon isn't just one girl - Manet paints her twice, and he is not doing so (as was traditionally done with multiple depictions) to imply the narrative of two separate events in her life. Like all of us, she is both the inner being of her self conscious mind, and the outer face she shows to the world, and both of those things are going on in her one body, her one mind, simultaneously. Clearly Manet understood that the rise of the camera freed artists to make art about how they felt, instead of just what they saw.

That is what makes this humble depiction of a seemingly insignificant figure one of the most important paintings of the 19th Century, and why it eclipses even Manet's previous (yet still very important) work.

Edouard Manet, who is rightfully called the Father of Modern Painting, made The Bar at the Folies-Bergere as the final, capstone painting of a pivotal career. It is the painting which bridges the Realist and Impressionist movements, and through it, Manet still communicates his understanding of classical painting, masterfully combined with the modernity of elevating contemporary bohemians and their interior lives as the subjects of high art.

Manet was a dandy, a man about town, a flaneur - who was well acquainted with the bourgeoise pleasures a nightclub like the Folies-Bergere had to offer. Well dressed, dapper, socially and (more than most other artists) financially secure, Manet was the first major male artist with the clarity to portray his female subjects as something other than a Queen, Madonna, or vacuous nymph. Manet painted ordinary, everyday, actual contemporary women with eyes that dared to look back at their viewers. In Les Dejeunner sur l'Herbe (1862-3), Olympia (1863) and Gare Saint-Lazare (1873), Manet convincingly painted women who who each purposely meet our gaze. Armored either by the power of their own self conscious nakedness or in the fashion of the day, Manet's women were not simply objects of socially acceptable prurience or piety; they were not objects at all. In the first truly modern paintings, Manet captured both his subject's bodies and their interior self awareness.

Manet's career was defined by both scandal and success. After a six year apprenticeship in the studio of Couture, Manet began to reject the formal, codified style of painting that was the cultural standard. Although he is classified as predominantly a realist, Manet went beyond the truth tellers like Courbet, Millet, and Daumier with a yet more vivid palette and considered abandon of their careful brushwork. With a loose hand, experimentation with perspective and light, and manipulation of color to flatten his forms, Manet began earnestly to lay the foundation for the Impressionists, and then, a century later, his "patches of paint" would open the door to Abstraction.

Instead of concentrating on neo classical historic, religious, fantastic or royal subjects, Manet (like the other Realists) chose to paint what he was seeing, but, more importantly, he also elected to convey for his audience the feelings that scene provoked. The frank honesty of his vision was often seen by the establishment as a deliberate shock. However, despite stinging criticism, Manet continued to make the kind of art that satisfied him, which later became a bridge from the Realists to the Impressionists.

Of course, he wanted acceptance, but was never willing (or even had to) pay the price of conformity. Although he chose never to exhibit with them, Manet was the de facto leader of the Impressionist group, meeting with them regularly to discuss the changes of a rapidly urbanizing and modernizing Paris, and the ideas about art, science, philosophy and culture that informed all of their work. At the end of his life, before the last, final grand effort of The Bar, Manet painted an exquisite collection of floral studies, which were probably influenced, at least in part, by the loose, painterly floral images created by his Impressionist friends.

With his genteel breeding and discrete personal life, Edouard Manet was a private, unknowable figure who publicly expressed his interior life and feelings through his brush. In the early 1880's, his carefully curated world began to crumble, as he began to deal with the incurable, degenerative effects of Syphilis. A common disease in that time before penicillin, Manet's first symptoms were leg pains, which he hid by adopting a fashionable cane. Unfortunately, his father had also died of the disease, so Manet knew what was coming. As the symptoms progressed, the artist lost the use of his legs, then became confined entirely before gangrene set in, and one leg was amputated in an unsuccessful attempt to save his life.

During that terrible time, Manet conceived and painted The Bar at the Folies-Bergere, much of it while seated and in great pain in his studio. He knew he was dying, and he poured into his canvas not only everything that he understood about art, but also everything he understood about what it meant to him to be alive. Manet did not live to see the influence that his work would have on all of the art that followed, nor did he know that the purposely self conscious paintings he rendered in the late 19th Century would cause a seismic shift that today is the cornerstone of contemporary art and culture.

Resources:

Art: EVERYTHING YOU NEED TO KNOW ABOUT THE GREATEST ARTISTS AND THEIR WORKS, by Susie Hodge, Published by Quercus books.

THE STORY OF PAINTING, by Sister Wendy Beckett, Contributing consultant Patricia Wright, Published by Dorling Kindersley Books in Association with the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

SECRET LIVES OF GREAT ARTISTS by Elizabeth Lunday, Published by Quirk Books

Gardner's ART THROUGH THE AGES (Western Perspective), 14th Edition, by Fred S. Kleiner, Published by Wadsworth Cengage Learning

Gardner's ART THROUGH THE AGES, 6th Edition, by Horst de la Croix and Richard G. Tansey, Published by Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Inc.

No comments:

Post a Comment